For the Love of Macavity

by

Kelly Meister-Yetter

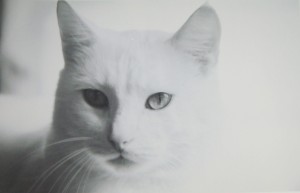

Macavity didn’t know he was supposed to be dying. Indeed, all the deaf white cat really knew was that he felt crummy, and that I would attend to his every need. Where his previous owner, my ex-boyfriend, had squandered his quality time with Macavity by spending a goodly portion of it at the dope house, I was the complete opposite: hovering nearby 24/7, I dealt with every sign and symptom of his liver disease the minute it revealed itself.

I acquired Macavity by default: after the breakup, his owner, having, apparently, nothing better to do with his time, began stalking me. I pressed charges and he was sentenced to several months in jail. Knowing that his alcoholic mother was in no position to care for Macavity, I offered to take the cat off her hands. I then moved across town, leaving no forwarding address. Macavity deserved better than he’d ever gotten with his neglectful first owner, and I was determined to rectify that.

The vet and his staff never let on that Macavity’s liver disease was terminal. They only told me how to treat it, with dietary restrictions, and daily sub-cutaneous infusions of saline solution. A life-long needle phobic, I actually embraced learning to do the sub-q treatments myself to save money, and the stress of taking Macavity to the vet every single day. He seemed to understand that I was trying to help him, and the only time he ever fussed about his treatments was when I forgot to warm up the bag of saline solution first.

As the months went by, Macavity’s condition deteriorated, but I kept pace with it. If he didn’t want to eat his kibble, I’d buy him a can of wet food, just to get something in his stomach. If he began to wobble off-balance late in the day – which meant that the toxic cooties were building up again more quickly than his liver could filter them out – I’d give him a second saline treatment. When he stopped grooming his coat, I groomed it for him, combing him multiple times each day, and cutting out the knots that had developed.

The vet’s staff told me that I’d know when it was time to euthanize. “How?” I’d ask them. “You just will,” they’d reply. Twice in the ensuing months, I called and asked the vet to come by and do the procedure, and twice, I called back and canceled. I just didn’t know for sure.

I found out much later that Macavity had only been expected to live for three months after his diagnosis. He was fifteen years old, thin as a rail, with a failing liver and constant diarrhea. Eventually, there was blood in his stool, too, and yet, like the energizer bunny, he kept on going. Every morning, he continued to get up and soldier through the day, until one morning, thirteen months after his diagnosis, he refused his food. He refused everything else I offered him, too, and I realized that “that” day was at hand. It was time. I called the vet’s office, and this time, I didn’t call back and cancel.

The vet was kind enough to do the euthanasia in my home. That was then, over a decade ago. I don’t know of any vet who would do it now. I felt strongly about at-home euthanasia because going to the vet’s was so stressful for Macavity: in addition to all the usual horrible smells, he couldn’t hear a thing; he could only see, and seeing all the other animals in the waiting room really frightened him. The fact that I was able to do this one last loving thing for him – help him pass in the comfort of his own home – gave me a small measure of peace.

I was in agony after his death. Suddenly, my purpose, my noble endeavor, was done, and I had very little reason to get out of bed anymore. Cheating death for so long had made me a little cocky. I knew that Macavity would eventually die, but it always seemed like something that would happen some vague, indeterminate time in the future. When the day actually came, I was not prepared for it at all.

I became aware of motion, then, and how the rest of the world seemed to go on at the usual pace while my little chunk of it slowed to a crawl. It was as if I was living in slow motion while the world around me hustled onward. The radio became a solace and an anguish: Phil Collins’s “You’ll Be in My Heart” had become our anthem, and the stations played it all day long. Tears would stream down my face every time I heard it, and I was sure that I would never feel happy again; Macavity had taken too much of my heart with him when he died.

Eventually, I found my footing again. It took several years. I started volunteering my photographic services to my neighborhood Humane Society, taking pictures of the animals that they offered for adoption. My activism snowballed from there to include rescuing and rehabbing animals in need, and advocating for a gang of abandoned flightless ducks who’d been dumped at a local pond. Fifteen years after Macavity’s death, I wrote my first book, an animal-themed memoir that detailed my experiences caring for a number of different critter species. The energy I spent ministering to Macavity all those years ago was now focused wherever I saw other animals in need.

Today, I carry on with my efforts rescuing and advocating for animals. I have four cats in the house, two rescue ducks in the yard, a lease horse at The Rescue Barn up the road, and whatever specie in need at a given moment enjoying the services of myself and my wonderful, put-upon, not-quite-as-enthusiastic-as-I husband. The good work, started out of love for Macavity, continues!